Important Notes from part 4 of the Interview of Dr. Deborah Burris-Kitchen by Dr. James Haney

DBK: They wanted more police officers on the street to fight this war on drugs. And they got their 100,000 more police officers.

There were a hundred thousand more police officers put on the street and those police officers were put in primarily, minority communities. To look for drug users and drug dealers; and they found them.

From there what I wanted to look at was from 65, where we stopped basically, before we started talking about what happened once freedoms were given that had been deserved and fought for, for so many years.

Once those freedoms were given, all of a sudden you see the arrest rates of African Americans which had remained at about 25 percent (anywhere from 25 and 30 percent) from 1934 when the UCR started collecting arrest rate data.

From 1934 'til about 1966 arrest rates remained at about 25 to 30 percent for African Americans. And their prison population was about 25 to 30 percent, so it matched their arrest population.

Well, from the middle sixties on, what happened is, you still have an arrest rate of African Americans that runs from 25 to 30 percent on a given year but yet their prison population is made up:

65 to 70 percent of our prison population is African American Now!

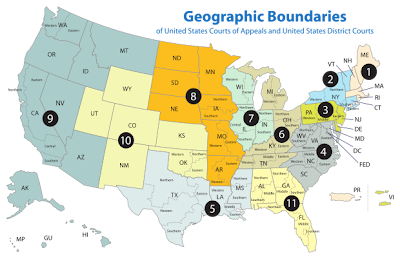

And if you look at the Federal Prisons and people who are in Federal prison for non-violent drug offenders: It's 85 percent of non-violent drug offenders who are in Federal prison are African Americans. And this is because of this war on drugs.

What my concern is, it's because of the whole issue of privatization of prisons as well, coming right along side of this.

Ok, we're arresting all the drug dealers. And of course the drug dealers are African Americans, which we know they're not. And they're not arrested any more; they're looking for the African American drug dealer, but they can't find him because they still only have an arrest rate of 25 to 30 percent but they've got all these police officers looking for them; they can't find them. So obviously that's not who's dealing drugs and not who's using it.

At the same time you've got these disparities and arrest vs. incarceration rates which it should be like this:

(Photo: Dr. Deborah Burris-Kitchen making a gesture with her hands of how the arrest vs. incarceration rate should be but telling us that it is not really that way)

(Photo: Dr. Deborah Burris-Kitchen making a gesture with her hands of how the arrest vs. incarceration rate should be but telling us that it is not really that way)but it's not. You've got privatization of prison. So you've got all these prisons opening up. And one in particular has opened up in Northern Virginia that used to be one of the largest slave plantations back in the 1800s in the United States.

They're taking all the prisoners from Washington D.C., which primarily is going to be about 90 percent African American and putting them in that prison in Virginia, which used to be slave plantation lane. They're doing and they're in private prisons doing labor for free -- In this private prison in Virginia -- African American males who are in there for non-violent drug offenses.

JH: This has also been a part of the system in the State of Tennessee as well, has it not? The private criminal systems and efforts on the part of some peoples to increase their numbers? Is that true in reference to your statement here?

DBK: Right. Correctional Corporation of America is probably one of the biggest prison systems. We have a -- Correctional Corporations is here in Nashville -- a parting place. And they are housing a lot of inmates.

The reason why people are voting for, and agreeing with, and not screaming about this privatization of prison looking a lot like slavery, is because it's coming under the umbrella of, well it's saving the tax payer's money. And we don't want to pay taxes to keep people locked up, so if the private prison can do it cheaper, let 'em do it.

What they don't understand is that the private prisons are incarcerating people for profit. They're going into these prisons and they're making clothing and they're booking their airline flights and they're getting credit card information off of people who are calling in to buy things. And prisoners are on the phone booking your airline flight and getting your credit card information. Which isn't a big concern to me because you know they're not going to do anything with that information.

JH: This is still an exploitation of labor.

DBK: Yeah. That was my concern. It's not that they were getting information. It's that they're doing labor, making profit for corporations.

JH: Which use them to expand the system itself.

DBK: If you're incarcerating people for profit, then you're going to want to put more and more people in prison. You're not going to want to solve crime. You're going to want to lock people up.

JH: That's what it's all about.

DBK: Right.